The Narwhal | News

September 29, 2020 | Sarah Cox

The Kaska Dena have a plan to protect caribou and other endangered species while preserving their way of life, but documents released to The Narwhal show the provincial government cast doubt on the proposed Indigenous protected area while flagging ‘very important’ mining activities and potential loss of revenue for forestry industry

Buying out mineral tenures for a Kaska Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area in northern B.C. could cost $24 million to $40 million, according to documents obtained by The Narwhal that throw cold water on a plan to protect a wildlife-rich area known as the “Serengeti of the North.”

The Narwhal obtained 20 pages of documents about the proposed protected area under freedom of information legislation. All but a four-page letter to the federal government — about the Kaska plan for a protected area in part of the nation’s territory — were redacted. In the letter, two assistant deputy ministers said there is “no cabinet mandate or commitment by the B.C. government to continue to add or designate new protected areas.”

“B.C. is currently unable to commit to establishing new protected areas,” said the November 2019 letter, signed by Jim Standen for the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy and Tom Ethier for the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development.

But just two months later, then-B.C. Energy Minister Michelle Mungall announced the NDP government was “working towards” creating the Qat’muk Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA) proposed by the Ktunaxa First Nation.

The Qat’muk protected area would sit in Mungall’s riding of Nelson-Creston in southeastern B.C., as well as in the adjacent riding of Columbia River-Revelstoke, held by the BC Liberals.

“That means at best the government has changed its mind about IPCAs or, at worst, it’s being inconsistent,” Dave Porter, a senior leader with the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, told The Narwhal.

“When Qat’muk was announced in January, then-Cabinet Minister Mungall said the agreement was ‘reconciliation in action and it is the right thing to do,’ ” said Porter, a member of the Kaska Nation.

“It was the right thing to do then, and it’s the right thing to do now and in the future, to work with other First Nations that want to partner with the government to conserve lands,” he said.

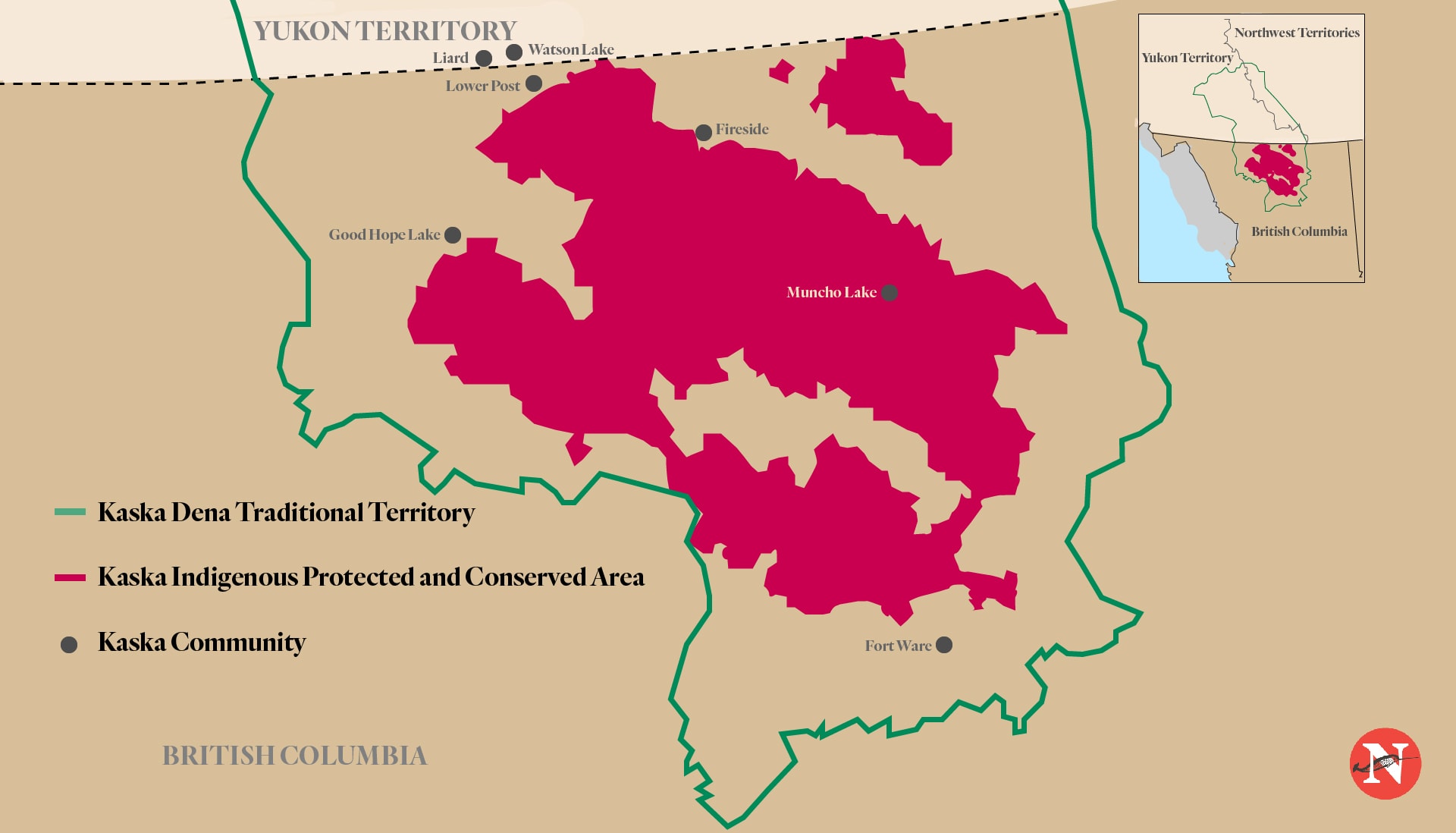

Proposed Kaska Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas are gaining recognition worldwide for their role in preserving biodiversity and securing a space where communities can actively practice Indigenous ways of life.

The Kaska Dena want to conserve a 40,000 square-kilometre area that would stretch roughly, tip to tail, from Lower Post to Fort Ware. The Kaska protected area would surround or connect to six existing protected areas, conserving watersheds and critical habitat for caribou and other species at risk of extinction while creating sustainable jobs.

The Kaska say the protected area is necessary to protect nature and preserve their way of life at a time when Indigenous cultures across the globe are threatened with extinction and when, every two weeks, somewhere on the planet, another language winks out.

Last September, Kaska chiefs travelled to Victoria to meet with Environment Minister George Heyman, Minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation Scott Fraser and Doug Donaldson, Minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development.

Six of the eight Kaska land guardians pose by the Liard River. The aftermath of a 2018 forest fire is visible in the background. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The meeting came after the federal government confirmed it would provide $587,500 to advance the Kaska protected area, one of up to 27 Indigenous protected and conserved areas supported through the Pathway to Canada Target 1 Challenge.

The Target 1 Challenge is a federal investment in expanding Canada’s connected and protected areas to meet the Trudeau government’s commitment — reiterated in the Sept. 23 speech from the throne — to conserve 25 per cent of Canada’s land and waters by 2025.

The letter from Standen and Ethier, written after the September meeting with Kaska chiefs, described the area proposed for a Kaska protected area as “very important for mining and mineral activities which support both local and provincial economies.”

A preliminary assessment indicates the Kaska proposal “may impact mineral potential, active mineral title and operations at the Silver Tip mine,” near the Yukon border, Standen and Ethier said. Additionally, there are 355 mineral claims and 21 placer claims within the proposed protected area, they stated.

“Forestry activities would be impacted in this area and loss of revenues would not be insignificant,” Standen and Ethier said, adding there are more than 46,000 hectares in the timber harvest land base.

“No work under any work plan should assume eventual protection designation,” the assistant deputy ministers told Ottawa.

Good Hope Lake in Kaska Dena territory. Photo: Maureen Garrity

Corrine Porter, executive director of the Dena Keyah Institute, a Kaska Dena non-profit organization, said the Kaska continue to work towards creating an Indigenous protected and conserved area in their territory.

“The Kaska Dena believe they have more than answered concerns raised in the letter over the past year and have no further comments at this time,” she said.

The letter to the federal government also describes IPCAs as a concept that remains “largely undefined,” a depiction challenged by Dave Porter.

“Far from being ‘undefined,’ IPCAs are widely known as major, Indigenous-led contributions to conservation and are viewed as an international model,” Porter said.

Three large-scale IPCAs have been created in Canada since 2018, including Thaidene Nëné (pronounced THIGH-den-nay NEN-ay), The Land of the Ancestors, one of the largest territorial protected areas on the continent.

In the Northwest Territories, the K’asho Got’ı̨nę people signed an agreement with the territorial government last November to establish and collaboratively manage the Ts’udé Nilįné Tuyeta (Ramparts) protected area to conserve wetlands, nesting grounds and lands of great cultural significance.

And in 2018, the Dehcho First Nations worked with the federal and territorial governments to create the Edéhzhíe Dehcho Protected Area and National Wildlife Area west of Yellowknife, in a region known as the nations’ breadbasket because its caribou, moose, fish and waterfowl have sustained people for millennia.

One of the earliest co-management arrangements with First Nations was crafted in B.C., where the Haida Nation and the B.C. and federal governments created Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site, Porter also pointed out.

“Governments across Canada increasingly recognize that IPCAs and Indigenous Guardians are effective tools for working together with First Nations to protect lands and waters and which support reconciliation,” he said.

In response to questions from The Narwhal, the B.C. environment ministry said in an email that, “Unfortunately, during the election period, government of B.C. communications are limited to public health and safety information, or statutory requirements.”

The Horse Ranch area of Good Hope Lake in Kaska Dena territory in northern B.C. Photo: Maureen Garrity

At a Sept. 28 leaders’ forum on nature and people, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau emphasized the importance of partnerships with Indigenous Peoples in meeting Canada’s conservation goals.

Trudeau’s comments followed the Sept. 15 publication of the United Nations Global Biodiversity Outlook, which says the international community has failed to meet 2020 commitments to reverse dangerous declines in animal and plant species. It calls for more emphasis on solutions, including expanding protected areas and augmenting the role of Indigenous Peoples in biodiversity strategies.

The letter from Standen and Ethier said B.C. had already achieved the Canada Target 1 goal of protecting 17 per cent of terrestrial lands and inland waters, estimating that 20.8 per cent of B.C.’s land base qualifies.

The letter also said there was “no cabinet mandate” for B.C.’s broad participation in the Canada Nature Fund program for new IPCAs “as B.C. has not only achieved but has surpassed the target” of 17 per cent.

“Notwithstanding this, B.C. recognizes that federal funding under this program does provide capacity and support that assists Indigenous Nations [to] explore their interests in land stewardship and management,” Standen and Ethier wrote.

Among the B.C. IPCA proposals supported by the Canada Target 1 Challenge is a plan by the Taku River Tlingit First Nation to create the Tlatsini “The Places That Make Us Strong” Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area. The nation is exploring conservation opportunities in its traditional territory including in the Taku, Whiting and Yukon river watersheds, which encompass vast areas of boreal forest and wetlands.

The letter said B.C. appreciated federal funding to assist the Kaska and the Taku River Tlingit “in identifying and developing interests that could come to future land use planning processes,” noting the B.C. government was not involved in land use planning with either nation.

Jordan, a Kaska land guardian, conducts water sampling along the Kechika River in northern B.C. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The area identified by the Taku River Tlingit contains significant mining and mineral resources, but is “less important” for oil and natural gas resources, Standen and Ethier noted. A full assessment of mineral potential in the area should be funded by Ottawa, they said, also noting that forestry in the area will require further assessment and analysis.

“Similar to mining and mineral implications, forestry impacts would need compensation for existing tenures and future lost revenues.”

Any assumptions related to a proposed Taku River Tlingit IPCA are “premature,” the letter said.

All costs associated with the establishment of protected areas as an outcome of the Canada Nature Fund, “should they occur, must be borne by the federal government,” Standen and Ethier noted.

The Qat’muk IPCA envisioned by the Ktunaxa Nation also received Target 1 Challenge funding. The Qat’muk IPCA would tentatively span about 70,000 hectares immediately north of the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy, including the Jumbo Valley and parts of adjacent watersheds.

Plans for the Qat’muk IPCA advanced in January after development rights were extinguished in the Jumbo Valley, where Glacier Resorts Ltd. had long planned to build a highly controversial ski resort in an area the Ktunaxa hold sacred as the spiritual home of the grizzly bear.

Privately held interests and tenures in the Jumbo Valley were purchased through a $16.2 million contribution from the federal government and $5 million from the Wyss Foundation, Wilburforce Foundation, Patagonia, Donner Canadian Foundation and Columbia Basin Trust.

Banner image: The proposed Kaska Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area in Kaska Dena traditional territory. Scientists say species will more easily adapt to climate change in areas such as this, where they can move from valley bottom to mountain top. Photo: Maureen Garrity